A 6-year-old boy created a game while sequestered indoors after the accident. Then his family made 300 copies.

Diane Sandnes was nervous about living only a few miles from a nuclear plant. So on March 28, 1979, when she heard there was an accident at Three Mile Island, she decided it was safest to keep her 6-year-old son, Adam, indoors.

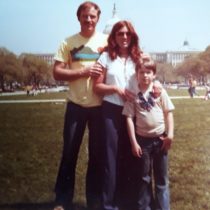

Courtesy of the Sandnes family. Edward, Diane and Adam Sandnes attend a Three Mile Island protest in Washington, D.C.

“We just didn’t like the reports coming out of there,” Edward Sandnes recalled. “We never kind of trusted government.”

The family followed news coverage, and Adam played to pass the time. At one point, he pretended two foam cups on the coffee table were the nuclear reactor’s cooling towers, and he come up with his own game inspired by the events unfolding around him.

When officials later recommended children stay inside, the family left Etters to stay with family in Williamsport. But after returning home, they revamped that foam cup game into something a little more produced.

Edward was a science teacher at York Catholic, so he incorporated his knowledge of reactors and cooling loops into the game. The family also created event cards based on news reports they had seen on TV.

Players roll two dice to make their way around the cooling loops, trying to avoid exposure to radiation as they travel. The game ends when the reactor reaches either cold shutdown or meltdown, and the player with the least accumulated radiation wins.

“The assembly of the game was done in our kitchen and living room,” Edward said. “We glued all the parts together by hand and we had, you know, all the cards had to be collated and you know, it was a massive project. We hand-built every game.”

The Sandnes family called it REACT-OR and made about 300 games. After shopping it around to family and friends, they approached local stores about putting up small displays. Each brought in a few more sales.

They sold about 100. Today, unsold boxes sit in the Sandnes’ attic. You can find a few copies elsewhere in central Pennsylvania, such as one in Dickinson College’s Archives and Special Collections, but it’s hard to find because it never reached mass production.

<iframe width=”560″ height=”315″ src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/G1IMN9rhSVc” frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture” allowfullscreen></iframe>

Edward wrote to game manufacturers like Hasbro and Parker Brothers. He heard back from only one company. The letter said they had in-house designers and did not need any outside help. Edward also wonders if releasing the game just months after the accident worked against them.

“Maybe it would be better now to try to sell the game because it’s in your past,” he said. “It’s not raw nerves.”

LINK: See photos of the game, hear TMI related music, learn more about TMI and pop culture