In March of 1979, I was 31 years old. I was living in Middletown as were my parents. I had graduated in 1973 from the Pennsylvania State University with a degree in journalism and had a part time job writing a weekly column for TV Host magazine, Harrisburg. [Please ignore the typos in the article as they were out of my control in the layout room before the advent of computer word processing]. I was also pursuing a career as an actor and had just come back from New York after a single walk on appearance on the TV soap opera, One Life to Live. I had a possibility of landing more work through a well-known casting director, but only if I relocated to New York City. My life path was completely altered by the accident at Three Mile Island.

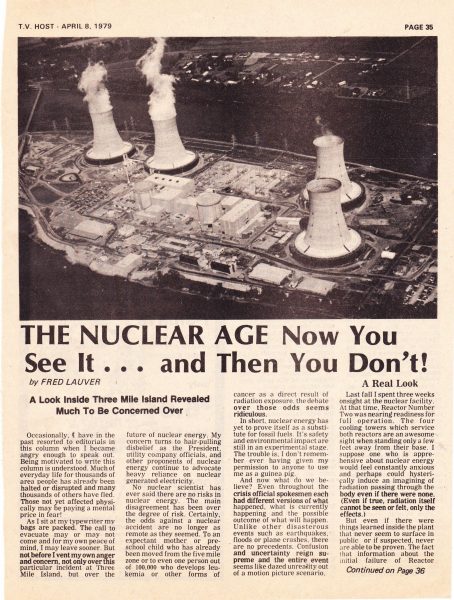

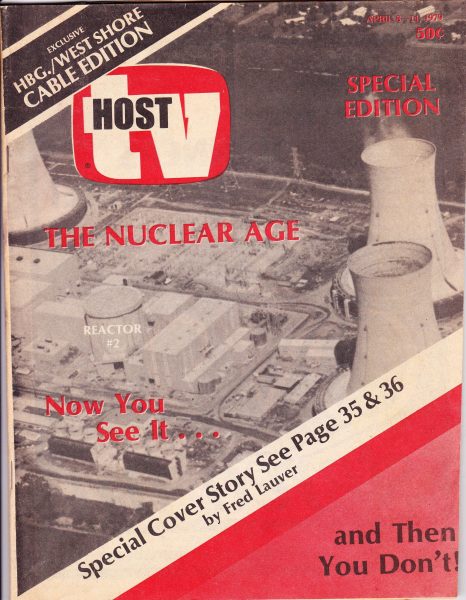

I have attached a cover story that I wrote, published on April 8, 1979, about the accident. In it, I describe my experiences and conclusions about nuclear energy and an experience of working temporarily inside the TMI plant. What I did not include were anecdotal experiences and observations that affected me directly, but I will summarize those events here.

no background check, no training

In the Fall of 1978, to supplement my income, I worked for a temporary employment agency. One of the jobs they assigned me was at TMI for about one week. My job task was to photograph and create new security badges for employees using photo and laminating equipment supplied by General Public Utilities. I am a veteran of the U. S. Air Force and possessed a Top-Secret security clearance, so I was highly aware when protocol did not match the importance of a site or information being protected. As a temporary employee, I was not subjected to any kind of background check and GPU did not prescreen me prior to my arrival at TMI. They were careful about their own regular employees, but not subcontractors. At the time, I suppose it was a calculated risk much in GPU’s favor, but I assume that today, they are much more careful about every person who enters the property of a nuclear generating plant. When I testified before the Nuclear Regulatory Commission later in 1979, I suggested that they do something to tighten security requirements in regard to subcontractors who come and go at nuclear plants.

In the Fall of 1978, to supplement my income, I worked for a temporary employment agency. One of the jobs they assigned me was at TMI for about one week. My job task was to photograph and create new security badges for employees using photo and laminating equipment supplied by General Public Utilities. I am a veteran of the U. S. Air Force and possessed a Top-Secret security clearance, so I was highly aware when protocol did not match the importance of a site or information being protected. As a temporary employee, I was not subjected to any kind of background check and GPU did not prescreen me prior to my arrival at TMI. They were careful about their own regular employees, but not subcontractors. At the time, I suppose it was a calculated risk much in GPU’s favor, but I assume that today, they are much more careful about every person who enters the property of a nuclear generating plant. When I testified before the Nuclear Regulatory Commission later in 1979, I suggested that they do something to tighten security requirements in regard to subcontractors who come and go at nuclear plants.

So, there I was, with no background check, no training other than about 15 minutes of operating the photo badge equipment. Most of the time I was there, I was NOT supervised. How easy would it have been to produce a fake security badge? Very easy! I was quietly incredulous about it, but fortunately for GPU, I would never even consider doing such a thing and would have reported anything suspicious. Perhaps I have an honest face, but they never questioned my work.

During a break, a plant supervisor invited us on a tour of Unit Number 1, as Number 2 was still under construction. The supervisor seemed to brag about Unit 2 being rushed to completion in order to take advantage of tax breaks with the expectation Unit 2 would be ready for operation by the end of 1978. I was also surprised during the tour to see the security door to Unit 1’s control room door propped open when it was supposed to be closed for security purposes. I was told that the room was too warm for workers, so they did that to cool the room down. On the very first day of my assignment, when I drove my automobile onto the island, security guards at the entrance gate did check my car thoroughly, and made me open my trunk. That was the only day they did so.

what if someone of ill intent had been hired to create those security badges?

On hindsight after the accident, my military training caused me to ask myself, what if someone of ill intent had been hired to create those security badges? They could have smuggled weapons in an unchallenged automobile, created security badges to gain access to critical rooms, and initiated sabotage of the nuclear plant. This scenario, of course, is not relevant to the accident. However, what it does is point to a more relaxed attitude that prevailed—in other words, the idea that nuclear power was perfectly safe and there is little chance of anything going wrong. If we recall that a mistake was made during the emergency that made the accident worse, one may wonder, with more rigid and demanding procedures, could the accident have been prevented?

The National Guard was on the streets of Middletown

I remember the uncertainty, conflicting information, and confusion surrounding the accident. I remember General Public Utilities spokesperson minimizing the accident before any facts were known. I had already been making plans to move to New York, but my parents were there in Middletown. I wasn’t going anywhere as long as they were there. But, they did have suitcases packed in case of an evacuation order. I remember one evening upon returning to Middletown after dark during the week of the accident. The National Guard was on the streets of Middletown and stopping vehicles coming into the town. Since my residence was there, it was no problem, but it seemed quite surreal and I never thought I’d see the streets being patrolled as though there was an invasion.

As an aside to this story, about six months prior to the accident, I had a very strange and vivid dream about TMI that I have not forgotten to this day. I dreamt I was in the parking lot of the Village of Pineford apartment complex where I lived when a cloud of radiation released from TMI came down on me. During the actual week of the accident, I came out of my apartment, got into my car and started my car, turned on the radio for the latest news, when the local radio station reported that a cloud of radioactive steam had just been released from TMI. Of course, in real life you could not see radiation. However, it struck me as an extremely surreal and weird coincidence that I was in the same exact place and exact time of day that was in my dream.

I was not about to abandon my family in the middle of a crisis.

Of course, I did receive the public body scanning that was offered to people to look for signs of radiation present in the body. The results were negative, but I also wondered if the machine was capable of finding trace amounts of radiation too small to detect, but still could cause damage to the body. About 15 years ago, I began to have problems with my thyroid gland. I was treated for hyperthyroidism, along with monitoring of my blood cells to look for any signs of trouble. I was told I had unusually enlarged white blood cells, so it required me to continue having my thyroid and blood cells analyzed. The blood specialist was concerned that I could be developing leukemia. Strangely, after about three years of treatment, the thyroid went back to normal and, so far, no further thyroid or blood cell problems have been detected. I cannot honestly say if my thyroid problems are related to TMI, but because of the accident, I cannot rule it out and my doctor warned me that my thyroid could become a problem in the future. I should note that my late mother and stepfather also had thyroid problems and other health issues (but not cancer).

The accident at TMI also impacted my career and was the subject of a successful lawsuit. While the details of the settlement, as part of the agreement, are confidential, I can say that there were real and demonstratable damages. I was not going to abandon my parents and go off to New York in the middle of a crisis at a time when we did not even know if our home would become uninhabitable, as broadcast in national news reports. I abandoned plans to move to New York and ignored the invitation of a casting director because I was not about to abandon my family in the middle of a crisis.

I continued to live in Middletown for nearly two more years as concerns about radiation were lessened. We were told by public officials that there was no reason to worry about radiation poisoning. However, since then, there are still studies that claim that it was much more serious than we were told. There is nothing, of course, I can do to erase my physical presence during that time period. This does show, that unlike storms, fires, or earthquake disasters, you can put lives and property back together and forget about any further harm from those events. A nuclear accident, however, leaves insidious and permanent potential to cause damages for the rest of a person’s life.

I do not remember giving anyone permission to treat me as a guinea pig.

It was this personal eyewitness experience, plus other experiences that have shaped my opinion about nuclear energy. At Penn State University, prior to the accident, I took a course in environmental science in which the risks, dangers, and existing problems in nuclear energy were discussed and studied in detail. In the U.S. Air Force, I became highly aware of chemicals and radiation that could cause permanent harm to all life forms. When my father was in the U.S. Army during the Korean War, he was an eyewitness to an atomic bomb test in the southwest United States. I testified at an NRC hearing in Middletown; met Jane Fonda and Tom Haydyn and witnessed her visit and news conference, ironically around the time of the release of her movie The China Syndrome; participated as an actor in a reenactment for CBS News, hosted by Connie Chung; and, more recently, became a part of the Facebook group, “Three Mile Island Survivors.” That group’s administrator, Jill Murphy Long, has been working on producing a film about the TMI event and discussed with me the possibility of being cast in a role with the film. That film is not yet begun production and the role is not certain, but I would welcome any opportunity. Long is herself a former local resident and survivor of TMI, including survival from a brain tumor. She is convinced that radiation from TMI was responsible. She has been very outspoken.

Nuclear energy in my opinion is a paradox. On paper, the technology has the potential of being a seemingly viable alternative to fossil fuels. However, technology in the hands of human beings who can be unintentionally fallible at best, presents a risk to populated areas. It’s a gamble that makes us all guinea pigs of science. I do not remember giving anyone permission to treat me as a guinea pig.

Fred