At the time of the accident, I was a reporter for WHP-TV 21. A few days before it began, my photographer told me I should go see The China Syndrome, a movie about an accident at a nuclear plant. So Tuesday night 3/27/79, I saw the film in a local theater.

Next morning, I walked into the newsroom and said to my photog, “You were right; the movie was great!” He just looked at me, without any expression, and said, “It’s happening here.” I said, “What do you mean?” And he said, “Go look at the wire” (referring to the AP and UPI teletypes that were a fixture in newsrooms of that era).

Damn! We’re at the center of the biggest story in the country!

The news was breaking that morning about the accident. We all thought, “Holy crap!” – and of course our assignment editor sent several of us to the area near the plant to get what we could from Met Ed, the company that owned TMI, and the local officials. By the end of that first day, I thought, “Damn! We’re at the center of the biggest story in the country!” Very exciting for a young journalist.

The second day, two CBS network reporters, Gary Shepard (who came to our area often when there was a story with potential national interest) and Richard (Dick) Wagner, arrived to work from our newsroom. CBS’s Diane Sawyer and, because Channel 8 was too far away, NBC’s Andrea Mitchell also joined us in our pit. Richard Threlkeld, who at the time was an ABC correspondent working out of Channel 27 across the street, came over often to chat with his colleagues from the other networks.

We were getting phone calls from other radio and TV stations from all over the world, to get our local, “inside” view. And I thought, “Damn! We’re at the center of the biggest story in the WORLD!”

The famed Jimmy Breslin came to town and set up shop at a desk in the Capitol newsroom (which used to be across from the top of the rotunda steps). Lots of other reporters, print and broadcast, squeezed into all available spaces there. Breslin wrote several colorful pieces for the New York Daily News during the time he held court in the newsroom.

I was splitting my time between working different angles in the areas near the plant and hanging around the Governor’s office (I shared the Capitol beat) to get whatever information was available – and it was barely controlled chaos. The first couple of days I split my time between trips to the Middletown and Lewisberry area and hanging out in the Governor’s office waiting for word on what the government’s response would be to the different developments at the plant.

“Every dose is an overdose!”

The Union of Concerned Scientists came to Harrisburg shortly after the accident began – don’t recall the day – and had a huge meeting and press conference at the Friends meeting house on 6th street. They wanted to impress on the public that the TMI radiation releases were, in their eyes, dangerous no matter how small. One of the scientists, Dr. Ernest Sternglass from Pitt, proclaimed, “Every dose is an overdose!” His words are still imprinted in my brain.

The folks at TMI Alert, a citizen group opposed to nuclear power, immediately gained a credibility they never had before. Their warnings of the dangers of a nuke plant seemed silly, far-fetched – until the accident.

We reporters and photographers were issued yellow clip-on stick dosimeters to see how much radiation we were exposed to in the air around us. Mine pegged (at the top level, which, as I recall, wasn’t all that high) a couple of times over the week-plus that we were to wear them.

“Holy sh*t – we might be in real danger.”

Then on day three, Friday, we had “the bubble” (a hydrogen gas bubble that formed inside of the Unit 2 reactor) and things suddenly got scary. CBS News actually chartered a bus that sat on 6th street outside of Broadcast Center (our building) to be ready in the event their crews (in addition to its reporters, CBS had several dozen support personnel there) would have to evacuate with little notice. And we thought, “Holy sh*t – we might be in real danger.”

CBS did an hour-long prime-time special report Friday with anchor Walter Cronkite (who was initially supposed to come to Harrisburg, but the network decided he was too valuable to risk being in the area in the event things went south quickly) in New York and the reporters on the ground here. Part of that special was to be a talk-back with Dick and Gary from our studio. And “the most trusted man in America” started the talkback with his guys in our studio with the opening line, “Gentlemen, what’s the mood of the hundreds of thousands of people being evacuated from the area tonight?”

I remember Dick and Gary looking at each other wide-eyed for a second, then both jumped in to talk at once to let Cronkite know there was no mass evacuation happening. Earlier that day, Governor Thornburgh had issued an evacuation order for pregnant women and preschool children located within five miles of the TMI plant.

And where were the evacuees sent? To Hersheypark Arena – which was within a 10 mile radius from the plant. I remember thinking that distance wasn’t going to make a hell of a lot of difference in exposure for those folks – but I went to the arena and covered the influx of frightened evacuees. Many were there, sleeping on cots on the area floor, for over a week.

The accident certainly made us think about value judgments: what material things were most important to us? Like many others at the time, I packed the trunk of my car with a few necessities but filled most of the space with things I’d want to take with me if I had to leave knowing it was possible I might never return: photos, letters, vinyl records, special personal mementos. It all seemed surreal. And those things stayed in my trunk for weeks after the accident. It took some time to feel comfortable with the idea that nothing was going to happen to make it necessary to leave on short notice.

we had a “Whoopee – we’re gonna die” party

Friday night after the CBS special, we had a “Whoopee – we’re gonna die” party (a reference to the Country Joe and the Fish song Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin-To-Die Rag – the lyrics were about Viet Nam, but they were also relevant to our situation) at a co-worker friend’s apartment in Enola. The network folks joined us. We all partied hard that evening; we needed the release.

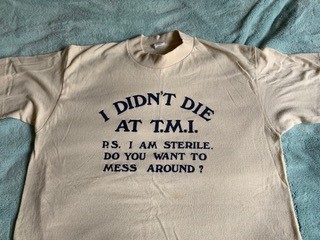

WHP CBS NEWS TMI T-SHIRT

The CBS folks stuck around Harrisburg for quite a while; I don’t remember exactly when the network guys left, but that bus was parked outside of the front door at Broadcast Center for days. One of the guys ordered special t-shirts for the occasion and gave each of us one as a souvenir; I still have mine.

TMI-themed T-shirts were big in local stores for some time after the accident. When I went to visit a friend in California that year, she requested that I bring her one. And I bought another style for myself.

My parents were going nuts and wanted me to come to their house in Wernersville to be safe, so since Saturday was my day off, I drove down in the morning to see them; my news director asked me to give him their phone number in the event he wanted to get in touch with me.

Early in the afternoon, the phone rang: it was my boss asking me to come back to work. So, over my folks’ objections, I drove back to Harrisburg. Weirdly, I felt better being back home, because that way I knew I’d be getting accurate information – something unfortunately in short supply with the international mob of reporters who had descended on the town reporting with varying degrees of accuracy.

I DIDN’T DIE AT TMI SHIRT

One of my favorite international contacts came from a radio station in Australia that had somehow decided to call our newsroom to get information. I answered the call; they asked if it were true that there was a meltdown at TMI and Harrisburg was wiped out. I said, “Well, you’re talking to me, and I’m in Harrisburg, so what do you think?” It was bizarro-world.

And I’ll always have a soft spot in my heart for Diane Sawyer, who gave me stringing work for CBS doing person-on-the-street interviews in Middletown. Nice to get a little extra cash – and exposure, even though TMI was the spark that made me decide to leave the news business a year later.

Hard to believe it’s been 40 years, because much of it is very vivid in my memory. I remember Met Ed’s president, Walter Creitz, and VP, Jack Herbein, being squirrely every time they spoke to the media, and I was frustrated with them due to their evasiveness and minimization of the situation. I recall feeling reassured by the NRC’s Harold Denton, who was the face of the NRC in the area for the duration of the accident – and one of the few people who inspired any confidence that the accident wouldn’t devolve to a worst-case scenario.

A few weeks after the accident, the China Syndrome was still playing in local theaters, and I went to see it again. There was a particular line that drew audience laughs the first time I saw it, but on this post-TMI second viewing, there was dead silence in reaction: the line was that a nuclear plant meltdown would “render an area the size of Pennsylvania permanently uninhabitable.”

It’s hard to explain how being in a situation where no one seemed to know what was happening, where no one was sure whether we’d still have homes to go back to in the event of an evacuation, and where something you can’t even see could hurt or kill you, affects you. I know that I’d never want my kids or grandchildren to know that helpless feeling.

Jan